Happy Halloween!

I was contacted recently by a reporter who was following up on the commonly repeated idea that belief in ghosts and hauntings is on the rise. She had found my Paranormal TV list and was interested in hearing if I thought paranormal media may have fed this rise. (Here is the resulting NY Times article.)

Well, this is not straightforward. First, is belief in the paranormal really increasing? And second, does the media feed the belief, or is the belief feeding the media? I’m confident that the interplay between belief and paranormal media is more complex and nuanced than assumed. Also, considering the times, maybe the polls are pointless.

We might measure “belief” by opinion surveys and polls, but these are not always readily comparable across the years. Different polling companies will pull from different sections of the public, and the way a question is asked will color the response. For example, TV networks will sometimes do a volunteer web pop-up survey of their audience asking “Do you believe in ghosts?” (or UFOs or Bigfoot, etc.) in association with promoting a new show or special with this theme. Unsurprisingly, the percentage of “yes” answers skews very high because the poll has drawn from those who already lean towards that type of programming. Most other popularity polls aren’t quite that biased but they aren’t always designed to accurately measure public opinion. (Consider the population difference between those available for a landline telephone survey vs an email-based survey.)

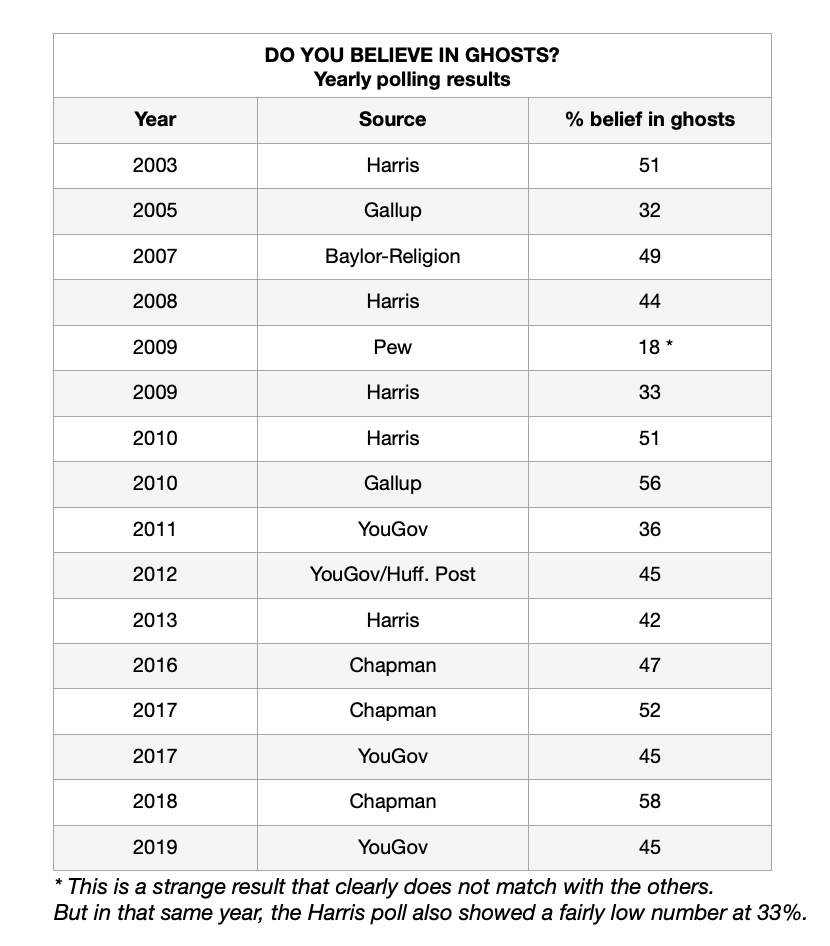

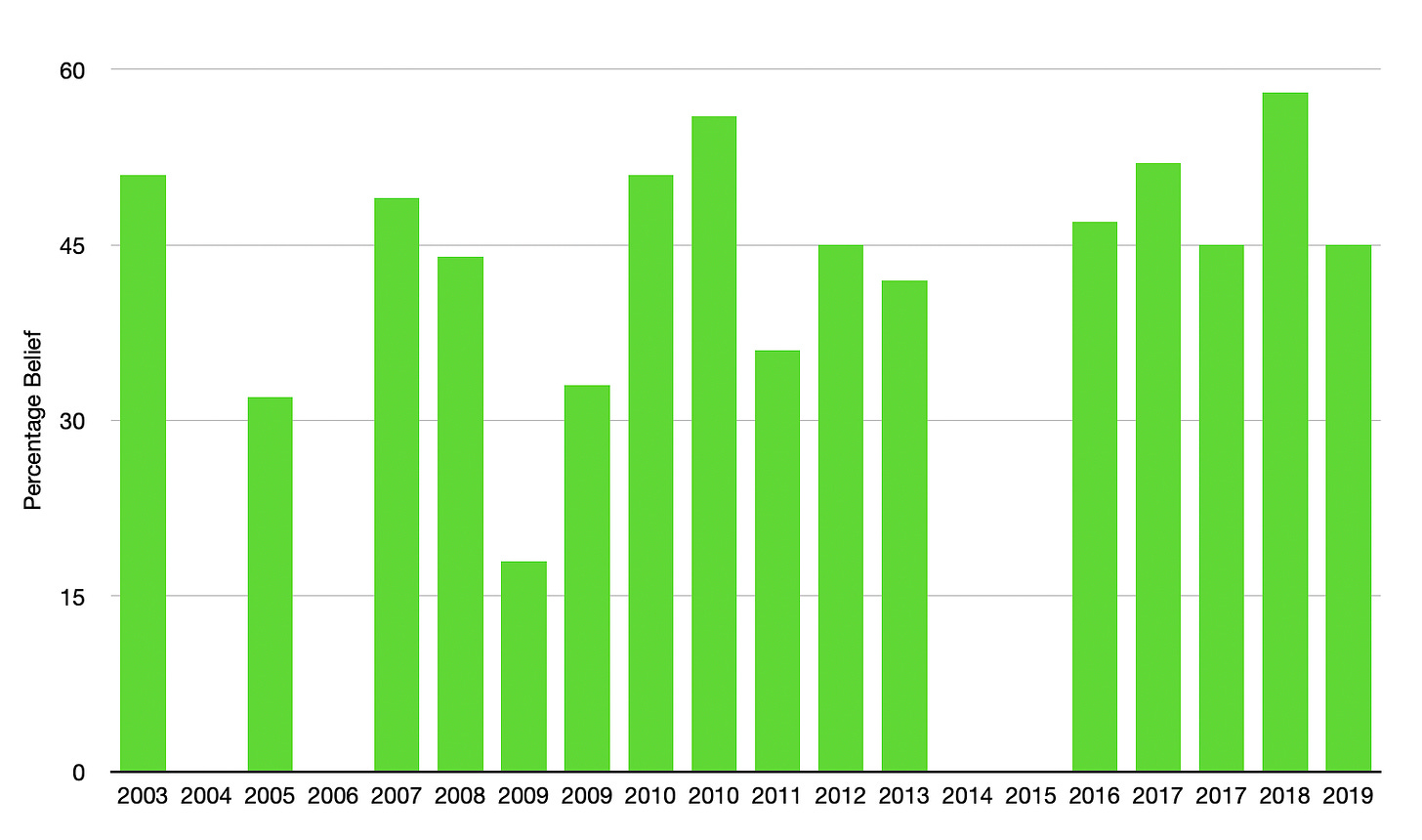

I quickly collected results from the major public opinion polls of the last two decades (Figure 1). I could find records from 2003-2019 with 2004, 2006, 2014, and 2015 missing. I only considered big polling companies. The results ranged from 18 to 58% positive belief. I’ve found no results for 2020 or 2021, but overall, especially in the most recent years, the value hovers around 45%. The results are fairly consistent but could be construed as trending slightly (but not dramatically) upwards. The percentage of respondents that “believe in ghosts” is sometimes a combination of “definitely believe” and “maybe believe” responses with the latter capturing more unsure people as believers. These less convinced respondents may very well be on the fence and answer differently depending on their mood, the season, or what news or media they last consumed.

I didn’t have ready statistics for surveys prior to this. But it’s generally accepted that belief in the paranormal was high in the early 1970s if we go by its popularity - mostly in printed media and TV specials. We can relate that to today with the ubiquitousness of paranormal media that encompasses more types of media available. We don’t see a whole lot going on in the early 80s.

Ghostbusters was 1984. This was the first time people saw paranormal investigators as heavily (and comically) technological. Ghost investigations have been ongoing since the 1860s. (Fact: It wasn’t invented by TAPS in 2004.) And, this field has ALWAYS been quite technology-heavy. But the gizmos and gadgets of Ghostbusters admittedly influence kids who are now adults, some of whom think that movie was almost a documentary.

In the 80s and 90s, it was not so socially acceptable to believe in ghosts. I’m not sure exactly what happened by the 2000s. A number of critical factors came together. It could be that the media influence took 15-20 years to manifest as the kids who saw Ghostbusters grew up. Influential programming like Sightings or Unsolved Mysteries and, in the UK, features like The Stone Tape, and Ghostwatch were certainly resurrecting interest in the paranormal. The equation is far more complicated than that, however. Previous research that attempted to measure the link between consumption of paranormal media and belief has been confusing and contradictory. People are complicated.

I tried to explain to the journalist that the 21st-century enthusiasm for ghost hunting displayed a few very important characteristics that likely underpins the high percentage of belief noted today. Since she expected someone to prattle on about the outrageous number of ghost TV shows, I think I gave her more of an earful than she bargained for. The plethora of paranormal programming, investigation groups, and advertised experiences exhibit these features.

Scienceyness. Ghost hunting “reality” shows emphasized the tech gadgets as necessary for any investigation. They used jargon and sciencey words and called themselves “professionals”. Over half said they used “scientific methods”. Their science was for show. But it was effective. The market for products aimed at paranormal investigators exploded. The interested person without a science background who knew nothing about the paranormal yesterday was readily convinced that it was a “fringe” or “cutting-edge science” and that you needed fancy devices to do it. That lent some seriousness and superficial legitimacy to the activity. (For more on this factor, check out my book, Scientifical Americans.)

Anyone can join in and DIY. It took no formal training, experience, or technical and scientific background to join in. You could make up a title and credentials and be recognized as an “expert”. The internet made this level of participation ridiculously easy. Affiliation offered by more infamous celebrity ghost hunting groups gave an additional boost of recognition and a sense of importance. Props to MTV’s Fear in 2000, the first show that heavily incorporated the first-person night-vision view and reaction cams that took viewers right along with the unfortunate explorer scaring themselves stupid. Anyone could do ghost hunting - even plumbers. Reality TV was basic, yet captivating. And, wow, did we get a flood of that stuff in spades. Ghost hunting groups took to making their own content via YouTube.

In your neighborhood. It wasn’t just the decrepit mansion that was haunted. Suddenly, ghosts were everywhere, even in your neighborhood. Average people were reportedly having haunting experiences. Sometimes they wanted to get on TV to show everyone. Sometimes the paranormal theme was a facade to hide mental or family problems. There were probably several investigation groups in your town that lent a sympathetic ear for a spooky story. Local haunted spaces were promoted for business and tourism like never before, which was a reversal of trying to downplay such rumors. Paranormal experiences were highlighted in local news coverage; they became almost common. Paranormal activity became a feature and was sought.

Questing for experiences and meaning. People were hungry to find spiritual meaning and have personal emotional experiences. They found (or created) mystery and haunted tales even in mundane places. People seemed to want to make a personal connection to the past and ghost legends were an effective means for this. Also, the decreased popularity of organized religion didn’t mean people became less spiritual. They found their own custom spiritual connection in ideas about ghost communication and life after death. Notably, we also saw a rise in paranormal pursuits in countries that are typically non-religious, like Norway and Sweden, so general enthusiasm about these ideas was widespread.

Social acceptability. Items 1-4 contributed to an overall increased social acceptability of ghost belief. Belief in ghosts used to go against conventional science, established religion, and cultural norms. Thanks to media and the internet, ghost research now appeared “scientifical”, and the dire religious warnings of past generations against paranormal topics seemed antiquated and silly. Clearly there was no real danger - everyone was doing it. Paranormal tourism and events exploded in popularity. Haunted themes are totally mainstream. Entertaining a belief in all sorts of bizarre entities is quite acceptable now. Those who are interested in these topics will find content aplenty. This content, shared all over the web, on TV, and in social settings, further entrenches the belief.

As the popularity of paranormal themes in everyday life spread, and the pretend-science technological approach became the norm, the quality of evidence for ghosts and hauntings never got any better. Almost no one reported full-body apparitions anymore, like in the olden tales. No one had solid evidence to throw in the face of naysayers despite a huge effort. Evidence related by the media of all types was still subjective and questionable - shadows, blurs, orbs, EVP, equipment oddities, and lots of anecdotes. While this kind of evidence is not (and never will be) enough to sway a scientific researcher, it was quite adequate to convince those who wanted to believe. The media does a fantastic job of reinforcing paranormal beliefs and even propagating new beliefs (like the specialness of 3AM or “going dark”).

In 2021, it’s probably never been easier to announce to the world that you believe in ghosts and have people agree with you. It seems harder to justify non-belief. The paranormal themes and stories are just SO ubiquitous, it becomes a chore to have to keep explaining your skepticism.

Since the 2000s, surveys of belief have floated around the 45% mark regarding ghosts and hauntings. Clearly, though, asking about “belief” is not altogether helpful and the responses in no way reflect the reality of spirits (or whatever ghosts might be). Instead, the survey answers are a commentary about modern society as a whole. While media is part of that, it’s part of the bigger equation, not the sole cause. We are searching for meaning, a special and unique experience to enrich our lives or to brag about with others. In many ways, immersion in paranormal themes feels like a way to connect to something beyond ourselves or our boring life. An experience can be powerful whether it’s real or imaginary. It doesn’t matter if you believe or not, you can’t avoid the cultural business of ghosts.

Check out: Sharon’s Ultimate Paranormal TV List and Scientifical Americans (Amazon print or Kindle)

If you are reading this on the web, consider subscribing.

Couldn’t agree more with this. In the simplest way of seeing it, I’ve always just assumed the media and the populace feed one another when it comes to paranormal belief. And the media doesn’t really want a complex or nuanced answer to the question of paranormal belief.

My jaded opinion is that they want whatever answer will feed their sound-bite machine so they can sell more of their papers/time slots/ web page hits, etc.

Making a serious study of this takes too much real work and they are most often not capable of doing the detailed work or interested in it, again, beyond a quick hit to please their reader/viewership. Media promotes the BS because they find a willing and receptive audience who, in turn, see their beliefs mainstreamed. As I mentioned, my jaded opinion only. But I doubt I’m too far off the mark.

You’ve written a terrific piece that does try to answer the question seriously, whether or not that journalist got more than she bargained for.